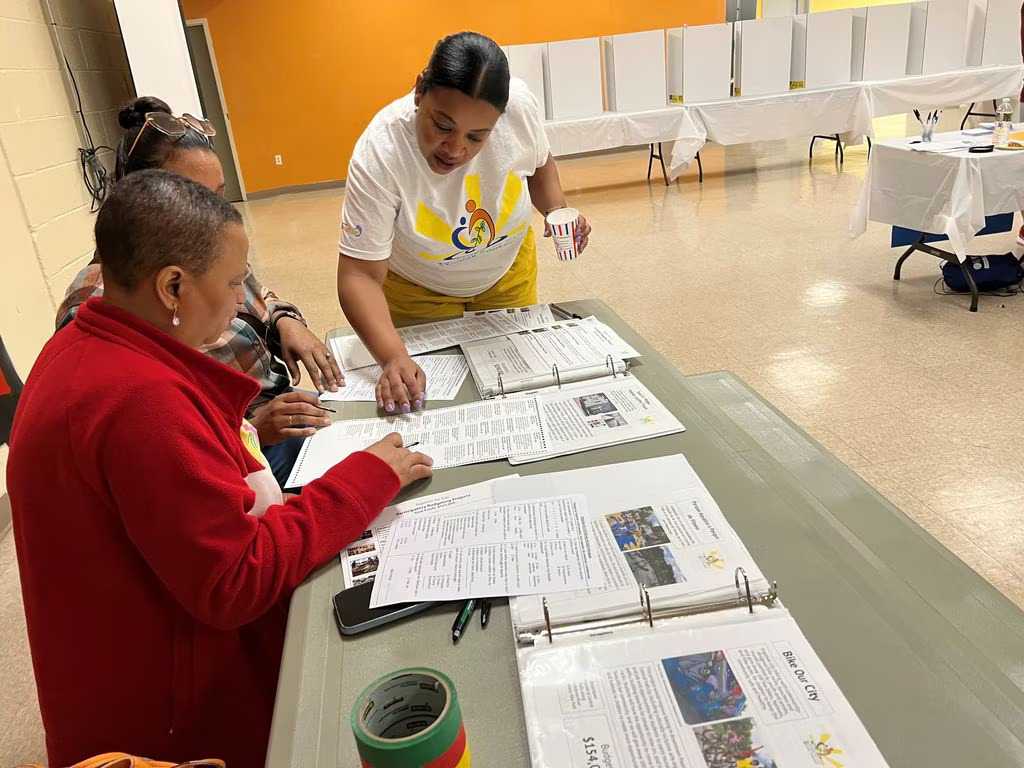

A group of residents from Central Falls and Pawtucket, R.I., look through the details of projects area residents designed that could be funded through a participatory budgeting process. LISC photo

Here’s what was funded, and how Rhode Island could adopt a participatory budget process in other areas of the state.

Last summer, residents of three Rhode Island cities were asked to figure out how to spend nearly $1.4 million.

Teenagers as young as 13 were asked to participate, all the way up to to adults well into their 70s. Some live not far from the neighborhood they grew up in. Others immigrated to the United States from Central America and Haiti. These communities — Central Falls, Pawtucket, and two zip codes in central Providence — also include undocumented immigrants who have never voted in a US election.

The participating communities are predominantly people of color, have historically been underinvested in, and are locations where COVID-19 and unemployment wreaked havoc.

The $1 million set aside for central Providence and the $385,000 for Pawtucket and Central Falls to share seemed like a ginormous amount of money that could solve a lot of problems — from rising housing costs to unpaid debt. On the other hand, these official federal dollars didn’t seem like enough to address their neighborhoods’ most blatant dilemmas to the extent that ordinary people — like themselves — would be affected.

But why residents to figure out solutions, instead of staffers at city hall? Becki Marcus calls it “direct democracy in action.”

“We’re creating a platform for residents to directly decide how they want to invest funds in their communities,” said Marcus, an assistant program officer at the Local Initiatives Support Corporation [LISC]. On a microcosm level, “This is exactly how democracy is supposed to work.”

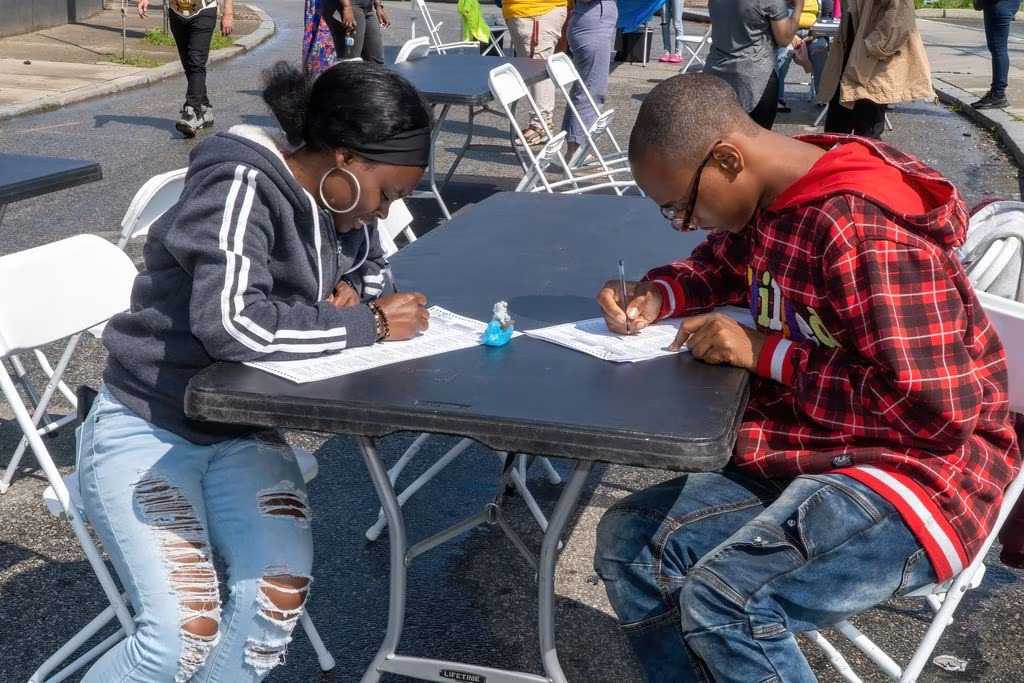

Residents in central Providence vote on neighborhood improvement and community projects in June 2023 in a participatory budgeting effort. STEPHEN IDE/ONE Neighborhood Builders

For the last year, these residents were engaged in a participatory budgeting process. It’s a method of democratic decision-making that has a long history in other countries, like Brazil, where governments call on ordinary people to decide how to allocate public dollars.

Rhode Island’s year-long process is part of a new initiative with the state health department’s Health Equity Zones (HEZ) initiative that uses a place-based, community-driven model to build resilient and healthy communities. Dollars came from a pool of Medicaid, federal, state, and private funds; and the state called on residents and workers in these communities to find out what they needed to live healthier lives, and which tangible investments could be made.

Over the course of several months, residents submitted more than 900 ideas to help address everything that would impact their health — from housing to food access. Those were whittled down with the help of partnering organizations (One Neighborhood Builders and the Nine Neighborhood Fund assisted the central Providence health equity zones. LISC assisted Central Falls and Pawtucket).

Earlier this month, residents cast their ballots online and on “election days” using real voting booths, to finally fund a handful of projects, which were exclusively announced to the Globe on Tuesday.

The winners included a new splash pad water installation at the John Street Park in Pawtucket. At Governor Lincoln Almond Park in Central Falls, which already has a playground for very young children, a new outdoor fitness equipment center will be set up in the coming months for older teens and adults. Those two projects will cost approximately $288,000. The remaining $97,000 will be used to develop and stand up a stigma reduction campaign for mental health. The program will create a multimedia campaign to bring awareness to metal health needs for people of all ages and cultures.

[text removed READ ORIGINAL STORY ON GLOBE WEBSITE]

In Providence, nearly $370,000 is being directed to install two new composting toilets at Merino Park, improve bathroom access at Donigian and Davis parks, and plant shrubs around the parks, to enhance green space. Another $330,000 will be directed to provide all households in the 02908 and 02909 zip codes who have lead-contaminated pipes with NSF-certified water filter dispensers.

Approximately $50,000 will be directed to launch a peer mental health training program for high school students in the central Providence neighborhoods, which is designed to help young people detect signs that their classmates and friends may be experiencing a mental health issue. Another $132,000 will be directed to improve bus stops.

Smaller projects were funded with $30,000 each: A bike distribution and repair workshop for low-income residents, a youth soccer program expansion, and an effort that will plant 20 food-bearing trees (like apples, pears, and nut trees) to help address food insecurity. Lastly, residents also voted to fund a life skills class for youth to discuss skills around personal finance, parenting, and domestic activities.

“These are the types of projects that will actually improve life for the people in central Providence,” said Anusha Venkataraman, the managing director of Central Providence Opportunities: A Health Equity Zone.

[text removed READ ORIGINAL STORY ON GLOBE WEBSITE]

Teens from central Providence vote on neighborhood improvement and community projects in June 2023 in a participatory budgeting effort. STEPHEN IDE/ONE Neighborhood Builders

Larger US cities, like in New York and Los Angeles, have started working participatory budgeting into finding ways to fund new neighborhood improvement projects. Earlier this year, high school students in Central Falls engaged with a participatory budgeting process to determine what upgrades their school needed with $10,000.

Proponents have lauded the citizen-engagement tool as a way to increase budget transparency and how citizens can feel more connected to their community and local government. Opponents say the process can be lengthy, and the types of neighborhood projects that ultimately get funded could have been overseen by a city department or manager.

Venkataraman, who moved to Rhode Island from New York City within the last year, said it took years for New Yorkers to “institutionalize” participatory budgeting, as it “requires a lot of folks outside of government to make it work.”

New York is “one example where with enough support and willpower, it can grow into something that people can expect to be able to participate in year after year,” she said. The process “is a special opportunity for residents to flex their power in such a real and tangible way.”