By Laurie Moïse, Director of Community Health Integration

“I do not trust the advice of my doctor.”

We frequently hear communities of color make statements of this nature. There are many reasons why these communities are reluctant to follow through on medical advice, including: a lack of minority presence in local medical practices; distrust of the health care system due to the historic maltreatment of persons of color, including unethical and deeply harmful experiments as well as stigma associated with various diagnoses. This profound barrier to equitable health care access dates back centuries—and persists strongly today.

Currently, with the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a dramatically higher rate of positive cases and deaths across the nation in communities of color than in White communities. At ONE Neighborhood Builders, we are working in community to combat the barriers our neighbors face with the support of the Rhode Island Department of Health’s Health Equity Zone (HEZ) Initiative. As the backbone agency in the Central Providence neighborhoods, we have been charged with addressing the public health needs of our communities. Most fundamentally, we believe that our neighbors need and deserve community-based health interventions that are culturally aware, informed, and responsive.

In the early months of 2020, the world began to shift due to the onset of the novel coronavirus. There was an urgent need for public health education across the globe—and skyrocketing demands on all health care systems. Government agencies and media outlets inundated us with hygiene education, including demonstrations of how to properly wash your hands and reminders to frequently use hand sanitizer. New demands on communication and public health education systems called for a swift pivot in how agencies communicate and share information across cultures. There was a call for an increased focus on low-income communities and urban areas that suffer from overcrowding and other significant barriers to health care to meet the need and help people stay safe.

It has been empirically demonstrated in numerous peer-reviewed studies in national and international medical journals that communities of color have suffered alarmingly high rates of health disparities across many illnesses throughout history, including a variety of serious chronic diseases, asthma, and infant mortality. This inequity has been fully revealed and highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that there is a disproportionate rate of COVID-19 positive cases in minority populations across the nation.

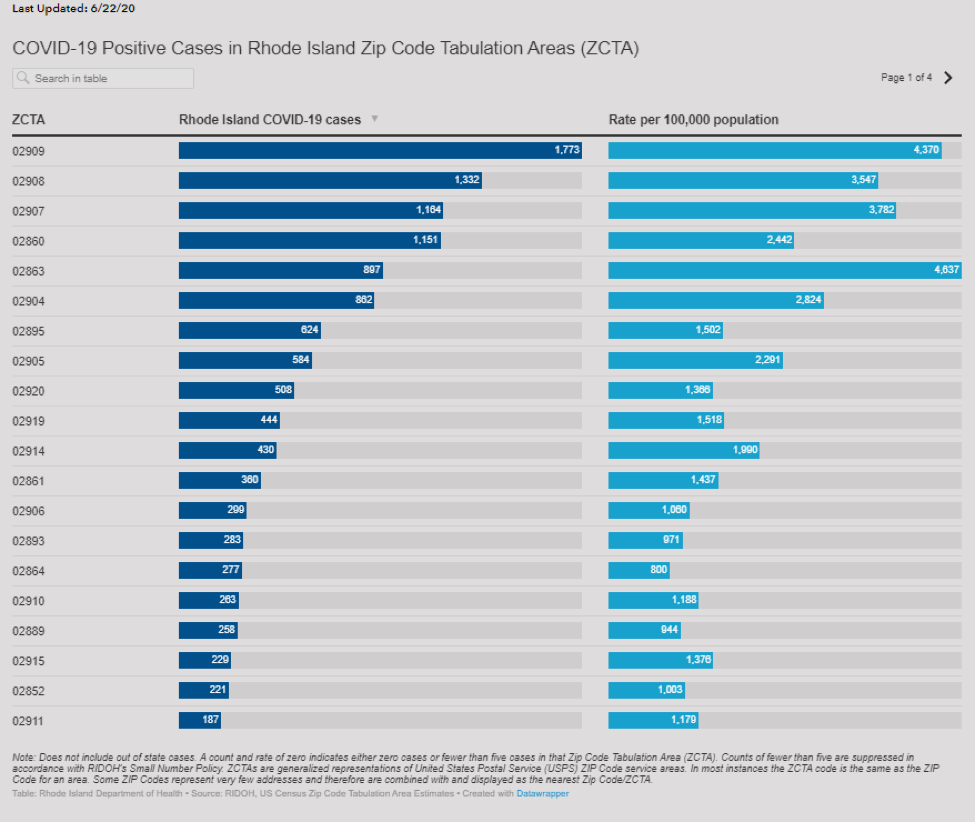

These highly disparate transmission and death rates are the result of individuals’ social determinants of health (SDOHs), which include: socioeconomic status, education, community, health care access, and neighborhood. As has been noted many times, people’s ZIP codes continue to determine how and how long they live. The graphic below, from the Rhode Island Department of Health, highlights how disproportionately this virus has affected our 02909 ZIP code/service area. We believe this to be an unacceptable and profound injustice, and we are working hard to eliminate it through our community-based CP-HEZ work.

Rhode Island’s COVID-19 data prove that within the state’s comparatively small minority population, there is a disproportionately higher rate of COVID-19 positive cases among Black and Hispanic people. As of the beginning of May, Hispanic/Latinx people represented 44% of the people who tested positive for COVID-19 and 33% of related hospitalizations, despite making up only 16% of Rhode Island’s population. The Black/African American population is also highly overrepresented in these areas: 13% of the state’s positive test results came from people who identify as Black/African American, despite that group making up only 6% of the state’s total population. More than twice as many people (47%) who tested positive for COVID-19 identify as Black/African American serve as health care workers than do White-identified people (22%). Looking at rates of transmission and hospitalization show approximately a fivefold higher rate among Black/African American (1,129 cases per 100,000 Rhode Islanders) and Hispanic/Latinx (911 cases per 100,000 Rhode Islanders) Rhode Islanders than among White residents (220 cases per 100,000 Rhode Islanders) and an approximately threefold higher rate of hospitalizations among the same racial and ethnic groups.

To meet vital and immediate community need, we have expanded our community health work across the Central Providence neighborhoods. The deployment of highly trained Community Health Workers (CHWs) in hard-to-reach neighborhoods has been a highly effective method to meet individuals where they are and assist in addressing health concerns on a more personal level. Though this has always been true, there is now an even greater need to immediately deploy a much greater number of Community Health Workers into our neighborhoods to meet basic needs of our community members and share public health education to cease the spread of COVID-19.

CHWs are residents of the community who serve as service providers and assist in addressing immediate and long-term needs of community members. Community health work dates to the late 1800s across the globe and is still being implemented in today’s health care industry. Historically, CHWs were referred to as storytellers, barefoot doctors, and farmer scholars, and by other monikers. Although CHWs have been named various titles in history, one thing has remained the same―CHWs have been those who served their very own community for the greater good. CHWs are defined by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention as:

(Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2015): “A community health worker (CHW) is defined as a frontline public health worker who is a trusted member of a community or who has a thorough understanding of the community being served. This relationship allows CHWs to serve as a link between health and social service programs and the community to promote access to services and improve the quality and cultural competence of service delivery.”

The work of CHWs has yielded improved community health worldwide, including in our own backyard. In 2019, the Central Providence Health Equity Zone created a cross-organizational partnership to deploy five CHWs in our Central Providence neighborhoods (Olneyville, Hartford, Valley, and Federal Hill). Our CHWs are charged with connecting residents to resources and advocating for the community. We have trained community members to work with their neighbors to address their social needs. The emphasis on community members being trained as CHW professionals is key in connecting community members to the appropriate resources and empowering our own neighborhood leaders.

Trust and cultural understanding guides the relationship between CHWs and community members, leading to success. Our CHW program is the first of its kind in our state. Through this cross-organizational partnership, we have leveraged numerous training opportunities for our team. We have also seen an abundance of aid given to our community members through this partnership and the relationships our team has built. Our partners include: Providence Housing Authority, Integra Care New England, Providence Community Health Centers, and Federal Hill House. The group of CHWs meets often and discusses and analyzes challenging cases. Due to the diverse knowledge the team brings from a variety of expertise, experiences, and perspectives, we can assess and direct residents in a responsive and culturally competent manner.

A few noteworthy successes of our CHW work include:

- Connecting various members of the community who are undocumented with care at Providence Community Health Centers and Clinica Esperanza due to their ability to see residents who do not have health insurance and/or immigration documentation;

- Residents were able to connect with Federal Hill House staff and receive food pantry items due to the connection between CHWs and that relationship; and

- Families with specific needs: diapers, ensure, specific dietary foods were able to get these items through our partnership and the relationships that have been built between CHWS.

As the director of community health integration, I supervise the efforts of our work in Central Providence. As a person of color myself, I understand the importance of having representation in all levels of direct service. Having a cultural connection is a key component to this work: I am proud to employ and work with community members who are willing to serve their own neighborhoods. Representation is so important. Being intentional about how we serve our neighbors with leaders who were recruited from and developed within their own neighborhoods will help us deliver better health outcomes and bring systemic changes to break the historic cycles that leave our low-income families of color at greater risk.