Thu, November 12, 2020 | by Ry Marcattilio-McCracken

Originally posted on November 12, 2020 at Muninetworks.org

When the pandemic hit American shores this past spring and cities around the country began to practice social distancing procedures, Rhode Island-based nonprofit One Neighborhood Builders (ONB) Executive Director Jennifer Hawkins quickly realized that many of those in her community were going to be hit hard.

As spring turned to summer, this proved especially to be the case in the Olneyville neighborhood in west-central Providence, where Covid-19 cases surged among low-income residents with fewer options to get online to work, visit the doctor, and shop for groceries. This, combined with the fact that the area suffers from an average life expectancy an astonishing eight years shorter than the rest of the state, spurred the nonprofit into action, and it began putting together a plan to build a free community wireless network designed to help residents meet the challenge. One Neighborhood Connects Community Wi-Fi hardware is being installed right now, with plans for the network to go online by Thanksgiving of this year.

How it Came Together

When Jennifer Hawkins started looking for solutions to the lack of connectivity in the area in March, she ran into a handful of other communities likewise pursuing wireless projects to close the digital divide, including Detroit, New York City, and Pittsburg. Along with One Neighborhood Builder’s IT partner, Brave River Solutions, she explored options and ultimately decided a fixed, point-to-point wireless network could succeed in the neighborhood. This was in no small part because ONB owns 381 apartments, 119 single-family homes, and 50,000 square feet of commercial and community space across Olneyville. It meant that two of the primary obstacles to standing up a fixed wireless network cheaply and quickly — finding suitable hardware installation locations and negotiating Rights-of-Way — were nonexistent, and a fast, less expensive design and rollout was possible.

ONB contracted with regional communications systems integrator Harbor Networks to do mapping, engineering, and design the network, with ADT hired to do hardware installations. Harbor Networks developed a heat map over the summer by walking up and down the Olneyville’s streets, identifying sight lines, picking hardware placements, and developing a plan to blanket the largest number of people with the fewest number of nodes. It picked routes for two underground fiber laterals (both terminating at ONB-owned buildings) to which 12 wireless access points would be connected, blanketing 2/3 of the neighborhood’s 6,900 residents with robust wireless. The Wi-Fi network will not only cover all of the organization’s affordable housing, but D’Abate Elementary School, the Joslin Rec Center, Joslin Park, and Riverside Park. Ocean State Higher Education Economic Development and Administrative Network (OSHEAN), which provides communications backhaul for the state’s k-12 schools, universities, and community colleges, will do so at the k-12 rate for the ONB project.

To fund the network, ONB launched a donation campaign and secured a host of backers. It secured CARES Act money from the state, and received contributions from private industry donors like the Tufts Health Plan, Baycoast Bank, Citizens Bank, the Washington Trust, the Rhode Island Department of Health, and 31 individual donors (including one large anonymous match) totaling more than $100,000. See the full list here. The initiative also has a donation portal for those looking to help.

Existing Health Disparities and Lower Connectivity Rates

One Neighborhood Builders is a Providence, Rhode Island-based community development organization founded 1988. Its website describes its mission as one which looks to “generate the social and economic conditions in central Providence that prolong life expectancy and work to eradicate systemic barriers that lead to health disparities. We lead the Central Providence Health Equity Zone, a collaboration of over 25 community stakeholders who work collectively to identify and eliminate barriers to health.” For the last 32 years it has focused on affordable housing development, serving as landlord, but also buying, fixing, and selling single-family homes and condominiums to area residents at affordable rates.

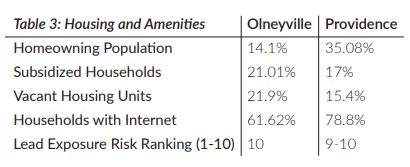

Olneyville served as a natural starting point for the ONB project, given its assets there and its focus on community health. In addition to the neighborhood’s shorter life expectancy and its struggle with having the second-highest per capita rate of Covid-19 cases (and the highest in absolute numbers) in the state, the Olneyville portion of the 02909 zip code also has a disproportionate number of residents earning a living through low-income jobs as essential service industry workers. Median family income is fully $17,500 below Providence’s, on average. Olneyville residents are more likely to live in poverty and be unemployed, and less likely to own personal vehicles or their homes.

The above, combined with the fact that the area has the lowest in-home rates of Internet access of any neighborhood in Rhode Island (61.8% compared to ~80% for the rest of the city) makes the neighborhood a prime candidate for intervention. It means bringing free, high-speed Wi-Fi to enable residents with low mobility and those suffering from chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension to visit the doctor and conduct their lives better in the midst of an ongoing pandemic.  In an interview, Hawkins called the last half year a “striking reminder of how important a social and economic determinant of health” Internet access can be. It’s “[s]omething pre-pandemic we would have considered an inconvenience,” but which “has become this meta issue when it is crucial to live, to learn, to work, [and] to connect with family members.”

In an interview, Hawkins called the last half year a “striking reminder of how important a social and economic determinant of health” Internet access can be. It’s “[s]omething pre-pandemic we would have considered an inconvenience,” but which “has become this meta issue when it is crucial to live, to learn, to work, [and] to connect with family members.”

Hawkins shared the things she sees that helped ONB succeed in the project: perhaps most importantly, because ONB owns all the buildings on which hardware is being installed, there are no ongoing lease costs or placement negotiations to make. Second, Olneyville is a particularly densely population neighborhood, covering just four-tenths of a square mile with about 6,900 people in multi-dwelling units housing from two to four families each. Third, most of the buildings in the area are of roughly the same height, making it well-suited for a point-to-point mesh network with clear lines of sight.

But the project has faced some challenges too. During the design phase, Harbor Networks wanted to go inside homes to calibrate signal strength, but didn’t due to the pandemic. This might mean some adjustments might be needed down the road. It has turned out to be a little more expensive than originally thought, too, and will run closer to $250,000 than the $200,000 the group originally planned.

Balancing coverage, speed, and reliability has also been a concern. “I want real Wi-Fi,” Hawkins said. “Not Panera Wi-Fi, not Bird’s Eye Park Wi-Fi. Students should be able to learn from home, parent’s should be able to work from home. That’s what I told engineers. I want what you have [at home].” Those in the green areas in the heat map above will see the fastest speeds, but the network is designed to deliver up to 20 Megabit per second (Mbps) symmetrical access to every household (with averages closer to 10 Mbps) at latencies of less than 200 milliseconds.

Online in Olneyville by Thanksgiving

ADT is installing the hardware on the buildings right now, and ONB is hoping to be done by Thanksgiving. The project will be using Ruckus switches, radios, and access points. One Neighborhood Builders will own the hardware, with operations conducted by Harbor Networks. It will be open to all residents in the neighborhood, and available both inside and outside of residences as well as in public spaces.

ONB is in the midst of getting the word out too, launching a public awareness campaign that includes interviews in the Boston Globe and on a local Spanish language radio channel (55% of the neighborhood identifies as Hispanic or Latinx) and a car parade with signs. ONB is also handing out brochures with instructions for residents to connect to the network once it goes online.

Looking Ahead

ONB Free Community Wi-Fi is a first-of-its-kind project in Rhode Island. “We were totally building the plane as we were flying it . . . We’re hoping we can be the instigator, so this can be genuine municipal Wi-Fi,” Hawkins said. Ongoing costs are projected at just $25,000 per year, and the nonprofit has committed to five years of support for the network. After that, they hope that the state or city can pick it up. But ONB also has plans to expand their efforts and reproduce the Olneyville network elsewhere in Providence, dependent on available funds. With its current design and setup, the two existing laterals have hit their capacity, but the group is already hearing from elected officials in nearby neighborhoods about how critical an issue Internet access has become for those in their communities.

This is not the first fixed wireless network we’ve seen materialize over the last half year. San Rafael, California built a similar network for its hard-hit Canal Neighborhood that went live at the end of August. Champaign, Illinois built a free wireless network for residents in one mobile home park where fiber ran up and down the streets, just a few dozen feet away. San Antonio is leveraging its existing network assets to beam city student Wi-Fi from stoplights. And McAllen, Texas is using government buildings, street lights, water towers, and 60 miles of fiber to provide more than three dozen neighborhoods with free public Wi-Fi.

But the Olneyville project is unique in that its origins lay in seeing free broadband as a health intervention with a measurable impact on community wellbeing. It’s a perspective we hope more communities will embrace not only in the midst of the ongoing pandemic, but in the years to come.

Originally posted on November 12, 2020 at Muninetworks.org